""While the world changes, the cross stands firm."

Showing posts with label Carthusian Spirituality. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Carthusian Spirituality. Show all posts

Monday, October 6, 2014

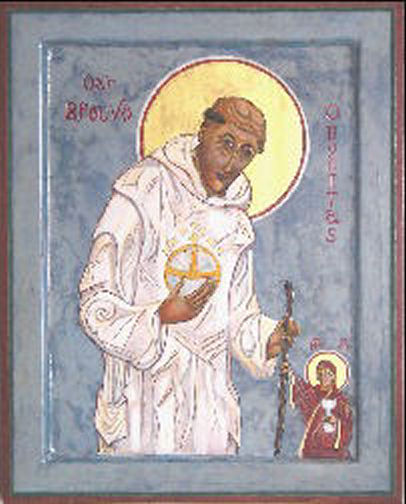

St. Bruno

Today, October 6, is the feast day of St. Bruno, founder of the Carthusian Order. While he is certainly nowhere near as famous as the saint we celebrated a couple of days ago (Francis of Assisi), because of my fondness for the kind of contemplative spirituality championed by St. Bruno, he is a particular favorite of mine. Plus, this quote from St. Bruno is pretty cool, too:

""While the world changes, the cross stands firm."

""While the world changes, the cross stands firm."

Monday, September 8, 2014

Death and Life (Monday Morning in the Desert)

Words from a recent sermon by Victoria Osteen, the wife of famous preacher Joel Osteen, have circled around the internet the past few weeks, and have been picked apart by numerous other bloggers and commentators, so I apologize for jumping on that bandwagon. (If you missed that story, the essence of her message was that we are to "do good for our own self" and not for God, because God just wants us to "be happy" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=koIBkYl0cHk).

In a world where Christianity has all but been eradicated in Iraq, where ancient Christian communities have worshiped for nearly 2,000 years, and where journalists trying to cover events in that region are being captured and beheaded, those types of messages emanating from American Christianity must seem quite peculiar to the rest of the world, to say the least. In the spirit of Martin Luther's commentary on the Eighth Commandment (the one about bearing false witness against our neighbor, according to the Lutheran/Catholic numbering of the Ten Commandments), I won't say more, except to just offer this quote from an anonymous Carthusian monk:

"Death to self and life in God are inseparably linked: the one without the other remains sterile." (From p. 43 of "The Prayer of Love and Silence".

In a world where Christianity has all but been eradicated in Iraq, where ancient Christian communities have worshiped for nearly 2,000 years, and where journalists trying to cover events in that region are being captured and beheaded, those types of messages emanating from American Christianity must seem quite peculiar to the rest of the world, to say the least. In the spirit of Martin Luther's commentary on the Eighth Commandment (the one about bearing false witness against our neighbor, according to the Lutheran/Catholic numbering of the Ten Commandments), I won't say more, except to just offer this quote from an anonymous Carthusian monk:

"Death to self and life in God are inseparably linked: the one without the other remains sterile." (From p. 43 of "The Prayer of Love and Silence".

Monday, August 25, 2014

Ask, Search, Knock (Monday Morning in the Desert)

Today's reflection comes from an anonymous Carthusian monk, regarding perseverance in prayer:

“Once we have understood that God is disposed towards us as

a father, confident perseverance in prayer is a natural consequence.

‘Ask, and it will be given you; search, and you will find;

knock, and the door will be opened for you.

For everyone who asks receives, and everyone who searches finds, and for

everyone who knocks, the door will be opened.’ (Luke 11:9-10).

The one who gives and opens is God. Ask, search, knock. Ask

for everything, ask for the Spirit, seek God, knock at the door of the Kingdom

(‘Lord, open to us,’ 12:25-7). Knock at

the door which is Christ, he who is the way to the Father; through his wounds

we have access to the Father, who, the first, is seeking after us in his Son. ‘Listen!

I am standing at the door, knocking; if you hear my voice and open the door, I

will come to you and eat with you, and you with me’ (Revelation 3:20). So, when

I pray, my prayer is only an echo of God’s prayer. In that case, how could he refuse, refuse

himself? What a mystery prayer is.”

(From “Interior Prayer” by a Carthusian, p. 29)

Monday, June 2, 2014

Interior Prayer (Monday Morning in the Desert)

Yesterday during worship, our Gospel reading was from John 17:1-11, and it contained what is known as the "high priestly prayer" of Jesus. It is a prayer which emphasizes the unity of Jesus with God the Father, as well as our unity with each other and with Christ.

As I have discussed before, the Carthusian order of monks is perhaps the closest thing we have in the Western tradition of the Church to the Desert Fathers and Mothers. The Carthusians teach that our ability to pray comes from the unity we have with Christ, and through the power of the Holy Spirit, our Advocate:

"Prayer is the respiration of our being, hidden with Christ in God. It is silence of the mystery that we are; or cry of the hope of things unseen, of a waiting which is not yet fully consummated. At such times, prayer rises from the depth of our heart, revealing to us who we are: a prayer that comes from beyond us, and yet which is within us, a prayer which is the manifestation of a love and a will which are mysteriously at one with God, and supremely efficacious. This is the work of the other Advocate promised by Jesus (John 14:17)."

(From the book, "Interior Prayer" by an anonymous Carthusian, translated by Sister Maureen Scrine, p. 80).

As I have discussed before, the Carthusian order of monks is perhaps the closest thing we have in the Western tradition of the Church to the Desert Fathers and Mothers. The Carthusians teach that our ability to pray comes from the unity we have with Christ, and through the power of the Holy Spirit, our Advocate:

"Prayer is the respiration of our being, hidden with Christ in God. It is silence of the mystery that we are; or cry of the hope of things unseen, of a waiting which is not yet fully consummated. At such times, prayer rises from the depth of our heart, revealing to us who we are: a prayer that comes from beyond us, and yet which is within us, a prayer which is the manifestation of a love and a will which are mysteriously at one with God, and supremely efficacious. This is the work of the other Advocate promised by Jesus (John 14:17)."

(From the book, "Interior Prayer" by an anonymous Carthusian, translated by Sister Maureen Scrine, p. 80).

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

Sleeping Like a Monk

Last night, the time change that occurred last weekend caught up with me (for readers outside of the U.S., we moved our clocks back one hour, ending Daylight Savings Time). I fell asleep on the couch at about 8:30 p.m., and got up and went to bed a little before 11 p.m.

Of course, I couldn't get back to sleep right away. Even though going back to sleep was what I desired, I could take comfort in two things as I was awake in bed: (1) I was actually following the natural sleep pattern of our ancestors, and (2) I had the opportunity to engage in the Biblical and monastic practice of praying at night.

Recent studies have shown that our bodies naturally prefer "segmented sleep", meaning two distinct periods of sleep at night. Roger Ekirch, a professor of history at Virginia Tech, has located numerous references in historical records to the time of "first sleep" and "second sleep" Before the Industrial Revolution and the widespread use of artificial lighting, our ancestors would go to sleep for a few hours after sundown, then would rise in the middle of the night for a few hours of activity, and then would fall back asleep until sunrise. So, my sleep pattern last night was perfectly natural. For more information about "segmented sleep", read this article: http://slumberwise.com/science/your-ancestors-didnt-sleep-like-you/

These recent studies are not news to certain monastic orders who follow the ancient patterns of prayer. For centuries, Carthusian monks have used our bodies' natural segmented sleep pattern to get up in the middle of the night to pray.

A Carthusian monk goes to bed at 7:30 p.m., and rises at 11:30 p.m. for a period of private prayer in his cell. At 12:15 a.m., the monks gather in the chapel for communal observance of the prayer offices of Matins and Lauds, which last approximately 2-3 hours, and then they go back to bed, where they remain until rising at approximately 6:30 a.m.

There are also numerous references in the Bible to the importance of prayer at night - "watching and waking":

"How often is it mentioned in the psalms that the person who prays 'meditates' (Psalm 1:2) on the law of God not only by day, but also by night, that he stretches out his hands to God in prayer at night, (Psalm 77:3, 134:2), that he rises 'at midnight to praise God because of his righteous ordinances' (Psalm 119:62)....

Christ was accustomed to spend 'all night. . . in prayer to God' (Luke 6:12), or 'in the morning, a great while before day' to go out in the wilderness to pray. (Mark 1:35).

Hence the Lord urgently admonishes his disciples, also, to 'watch and pray' (Mark 14:38, Luke 21:36), and indicates a new reason for it: 'You do not know the time' of the return of the Son of Man (Mark 13:33) and could therefore, weakened by sleep, 'enter into temptation.' (Matthew 26:41)."

(From pp. 79-80 of "Earthen Vessels: The Practice of Personal Prayer According to the Patristic Tradition" by Gabriel Bunge, O.S.B.).

So, the next time you have a bout of insomnia like I did last night - don't fret - take advantage of the time you are awake, and pray like a monk.

UPDATE (11/7/13): This article has been cross-posted on the Living Lutheran!

http://www.elca.org/en/Living-Lutheran/Blogs/2013/11/131107b

Of course, I couldn't get back to sleep right away. Even though going back to sleep was what I desired, I could take comfort in two things as I was awake in bed: (1) I was actually following the natural sleep pattern of our ancestors, and (2) I had the opportunity to engage in the Biblical and monastic practice of praying at night.

Recent studies have shown that our bodies naturally prefer "segmented sleep", meaning two distinct periods of sleep at night. Roger Ekirch, a professor of history at Virginia Tech, has located numerous references in historical records to the time of "first sleep" and "second sleep" Before the Industrial Revolution and the widespread use of artificial lighting, our ancestors would go to sleep for a few hours after sundown, then would rise in the middle of the night for a few hours of activity, and then would fall back asleep until sunrise. So, my sleep pattern last night was perfectly natural. For more information about "segmented sleep", read this article: http://slumberwise.com/science/your-ancestors-didnt-sleep-like-you/

These recent studies are not news to certain monastic orders who follow the ancient patterns of prayer. For centuries, Carthusian monks have used our bodies' natural segmented sleep pattern to get up in the middle of the night to pray.

A Carthusian monk goes to bed at 7:30 p.m., and rises at 11:30 p.m. for a period of private prayer in his cell. At 12:15 a.m., the monks gather in the chapel for communal observance of the prayer offices of Matins and Lauds, which last approximately 2-3 hours, and then they go back to bed, where they remain until rising at approximately 6:30 a.m.

There are also numerous references in the Bible to the importance of prayer at night - "watching and waking":

"How often is it mentioned in the psalms that the person who prays 'meditates' (Psalm 1:2) on the law of God not only by day, but also by night, that he stretches out his hands to God in prayer at night, (Psalm 77:3, 134:2), that he rises 'at midnight to praise God because of his righteous ordinances' (Psalm 119:62)....

Christ was accustomed to spend 'all night. . . in prayer to God' (Luke 6:12), or 'in the morning, a great while before day' to go out in the wilderness to pray. (Mark 1:35).

Hence the Lord urgently admonishes his disciples, also, to 'watch and pray' (Mark 14:38, Luke 21:36), and indicates a new reason for it: 'You do not know the time' of the return of the Son of Man (Mark 13:33) and could therefore, weakened by sleep, 'enter into temptation.' (Matthew 26:41)."

(From pp. 79-80 of "Earthen Vessels: The Practice of Personal Prayer According to the Patristic Tradition" by Gabriel Bunge, O.S.B.).

So, the next time you have a bout of insomnia like I did last night - don't fret - take advantage of the time you are awake, and pray like a monk.

UPDATE (11/7/13): This article has been cross-posted on the Living Lutheran!

http://www.elca.org/en/Living-Lutheran/Blogs/2013/11/131107b

Monday, October 21, 2013

Is the Rule of St. Benedict Supported by the Bible?

A common question posed by Protestants about any Christian belief or practice is: "But where is that found in the Bible?" This post is not about the merits (or lack thereof) of sola scriptura (scripture alone); instead, it will set forth a few ways in which the core of the Benedictine way is supported by the Bible.

One verse sums it up: "They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers." (Acts 2:42).

How does that verse relate to the essence of the Rule of St. Benedict? Acts 2:42 can be broken down into three parts: (1) "They devoted themselves to the apostles' teaching and fellowship" - this is found in various Benedictine devotional practices, such as lectio divina ("divine reading"). (2) "The breaking of bread" - the Rule of St. Benedict emphasizes the importance of the Eucharist. (3) "The prayers" - this brief mention needs further explanation, but there is a direct parallel between the pattern of daily prayer used by the first Christians, and the later daily office of prayers set forth in the Rule of St. Benedict.

This note in the Orthodox Study Bible helps explain the reference to "prayers" in Acts 2:42: "Prayers is literally 'the prayers' in Greek, referring to specific liturgical prayers. The Jews had practiced liturgical prayer for centuries, the preeminent prayers being the Psalms. Because the Psalms point so clearly to Christ, Christians immediately incorporated them into (New Testament) worship."

With that background in mind, other Biblical references to the daily liturgical prayers, which were incorporated into the Rule of St. Benedict, become obvious:

"One day Peter and John were going up to the temple at the hour of prayer, at three o’clock in the afternoon." (Acts 3:1). The apostles were praying the mid-afternoon prayers, later referred to by Benedictines as the office of "None".

"In Caesarea there was a man named Cornelius, a centurion of the Italian Cohort, as it was called. He was a devout man who feared God with all his household; he gave alms generously to the people and prayed constantly to God. One afternoon at about three o’clock he had a vision in which he clearly saw an angel of God coming in and saying to him, ‘Cornelius.’ He stared at him in terror and said, ‘What is it, Lord?’ He answered, ‘Your prayers and your alms have ascended as a memorial before God.'" (Acts 10: 1-4 - see also the reference at Acts 10:30). Here, Cornelius is praying the mid-afternoon prayers when he had the encounter with an angel.

"About noon the next day, as they were on their journey and approaching the city, Peter went up on the roof to pray." (Acts 10:9). Noontime prayer in the Rule of St. Benedict is referred to as "Sext".

"About midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns to God, and the prisoners were listening to them." (Acts 16:25). Here, they were praying the night office of "Vigils" - some monastic orders, such as the Carthusians, still pray at midnight. While most Benedictines have adjusted the time frame, they still pray the night office of prayers.

And how far back does the tradition of praying seven times a day go? At least as far back as the Psalms: "Seven times a day I praise you for your righteous ordinances." (Psalm 119:164).

Sometimes, this daily prayer ritual, observed by the apostles and followed to this day by Benedictines and other orders, is referred to as the "sanctification of time" - the hours of the day are made holy by prayer. For those of us who do not live in a cloister, and who have secular jobs, observing the seven daily prayer offices will not be feasible. However, given the Biblical precedent revealing the importance of regular daily prayer at different times, it should be a goal of all Christians - not just monastics - to figure out a daily prayer regimen that works for them, and follow it.

(Thanks to Matthew Dallman, author of the excellent book "The Benedictine Parish" - reviewed at http://benedictinelutheran.blogspot.com/2013/05/the-benedictine-parish.html - for highlighting the relevance of Acts 2:42 to the Benedictine way).

One verse sums it up: "They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers." (Acts 2:42).

How does that verse relate to the essence of the Rule of St. Benedict? Acts 2:42 can be broken down into three parts: (1) "They devoted themselves to the apostles' teaching and fellowship" - this is found in various Benedictine devotional practices, such as lectio divina ("divine reading"). (2) "The breaking of bread" - the Rule of St. Benedict emphasizes the importance of the Eucharist. (3) "The prayers" - this brief mention needs further explanation, but there is a direct parallel between the pattern of daily prayer used by the first Christians, and the later daily office of prayers set forth in the Rule of St. Benedict.

This note in the Orthodox Study Bible helps explain the reference to "prayers" in Acts 2:42: "Prayers is literally 'the prayers' in Greek, referring to specific liturgical prayers. The Jews had practiced liturgical prayer for centuries, the preeminent prayers being the Psalms. Because the Psalms point so clearly to Christ, Christians immediately incorporated them into (New Testament) worship."

With that background in mind, other Biblical references to the daily liturgical prayers, which were incorporated into the Rule of St. Benedict, become obvious:

"One day Peter and John were going up to the temple at the hour of prayer, at three o’clock in the afternoon." (Acts 3:1). The apostles were praying the mid-afternoon prayers, later referred to by Benedictines as the office of "None".

"In Caesarea there was a man named Cornelius, a centurion of the Italian Cohort, as it was called. He was a devout man who feared God with all his household; he gave alms generously to the people and prayed constantly to God. One afternoon at about three o’clock he had a vision in which he clearly saw an angel of God coming in and saying to him, ‘Cornelius.’ He stared at him in terror and said, ‘What is it, Lord?’ He answered, ‘Your prayers and your alms have ascended as a memorial before God.'" (Acts 10: 1-4 - see also the reference at Acts 10:30). Here, Cornelius is praying the mid-afternoon prayers when he had the encounter with an angel.

"About noon the next day, as they were on their journey and approaching the city, Peter went up on the roof to pray." (Acts 10:9). Noontime prayer in the Rule of St. Benedict is referred to as "Sext".

"About midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns to God, and the prisoners were listening to them." (Acts 16:25). Here, they were praying the night office of "Vigils" - some monastic orders, such as the Carthusians, still pray at midnight. While most Benedictines have adjusted the time frame, they still pray the night office of prayers.

And how far back does the tradition of praying seven times a day go? At least as far back as the Psalms: "Seven times a day I praise you for your righteous ordinances." (Psalm 119:164).

Sometimes, this daily prayer ritual, observed by the apostles and followed to this day by Benedictines and other orders, is referred to as the "sanctification of time" - the hours of the day are made holy by prayer. For those of us who do not live in a cloister, and who have secular jobs, observing the seven daily prayer offices will not be feasible. However, given the Biblical precedent revealing the importance of regular daily prayer at different times, it should be a goal of all Christians - not just monastics - to figure out a daily prayer regimen that works for them, and follow it.

(Thanks to Matthew Dallman, author of the excellent book "The Benedictine Parish" - reviewed at http://benedictinelutheran.blogspot.com/2013/05/the-benedictine-parish.html - for highlighting the relevance of Acts 2:42 to the Benedictine way).

Sunday, October 6, 2013

The Feast of St. Bruno, Founder of the Carthusian Order

In the Catholic Church, today is the feast day of the founder of the Carthusian order, St. Bruno (Unfortunately, he is not recognized on the Lutheran calendar). Since the Carthusians are strict vegetarians, I wonder how they celebrate a feast? An extra helping of peas?

Anyway, I've written before about my admiration for the Carthusians (see "Carthusian spirituality" posts http://benedictinelutheran.blogspot.com/search/label/Cathusian%20Spirituality), but I have not written much yet about their founder, St. Bruno. He was born in Cologne, Germany, and lived from approximately 1030 - 1101 A.D. Once a professor of theology, he refused an offer to become an archbishop, and began to live as a hermit. Eventually, this led to the beginning of the Carthusian order.

The Carthusians remember him as "having a profound influence over others.... (and) regard him as a spiritual master. He did not transmit more or less esoteric techniques. The structure of the life he lived with his companions is drawn from the classical monastic tradition: hermitages grouped after the fashion of a Palestinian lavra of the early centuries, a solitude in reality, but with the reinforcement of a common life on the one hand, and on the other, certain liturgical offices in common each day. Their piety was fed by the common resources of the Church: the liturgy, the sacraments, the Word of God, Christ.... Bruno saw a life dedicated to the contemplation of God, not as a sacrifice that impoverished, but as the one thing most useful for a human being, the response to our deepest and most real needs." (From "The Call of Silent Love", pp. 7-9).

Saturday, July 27, 2013

A Truly "Radical" Faith

The word "radical" is so over-used in modern Christianity that I suspect the word has lost its ability to convey a sense that something is extreme or shocking. Liberal and emergent Christians like to talk about "radical inclusion" or "radical welcome." Evangelicals talk about "radical discipleship." Lutherans talk about "radical grace." Sometimes I wonder whether the word "radical" has been used to the point that the word has become a cliche, and therefore isn't very "radical" anymore.

So, with that in mind, I usually hesitate to use the "r" word when writing or talking about Jesus, the Church, or Christianity in general.

But, I recently came across a new use of the "r" word when I reached the final few chapters of "The Call of Silent Love" - a book by Carthusian monks who live a life of solitude (if you click on the "Carthusian Spirituality" label at the bottom of this post, you will be linked to my earlier posts about the Carthusians). If anyone has the right to use the word "radical" in connection with their faith, it is the Carthusians.

The Carthusians use the word "radical" to explain the life-changing effect that God's grace has on our lives (I've highlighted the "r" word when it us used):

"The Christian, through union with Christ in baptism and sanctifying grace, participates in the life of Christ. We receive within ourselves a new life-principle, the Holy Spirit, new faculties for knowing with God's knowledge and loving with God's love. The light of faith opens on to the mystery of the human being and God. The unfolding of this life at once assumes and surpasses natural human life; in this we see our deepest desire fulfilled although it is hidden and cannot be realized by natural powers alone.

There is both continuity and radical disjunction. In the deepest reality of the human face is traced the image of God, thanks to an increasingly profound conformity with Christ, effected interiorly by the Spirit (2 Corinthians 3:18). Up to this point the self had struggled for self-affirmation in all the riches of its personality. The Gospel demands that we lose our life to gain it, so that it may be 'no longer I but Christ who lives in me.' The center around which our being is organized is henceforth no longer our self but Christ.

At every level there is radical transcendence. Let us go through the list from top to bottom. The great strength of affirmation and aggression that is found in us reaches paradoxical fulfillment in self-abnegation, obedience, gentleness, humility, and forbearance. The lust for possessions ends in the freedom of voluntary poverty, the thirst for knowledge in silence before the mystery, the desire for communion of love in the purity of the total gift of self to the Other." (pp. 167-68, 170)

"Radical transcendence" - that's a use of the "r" word I think I can accept. Let's just hope I don't over-use it.

So, with that in mind, I usually hesitate to use the "r" word when writing or talking about Jesus, the Church, or Christianity in general.

But, I recently came across a new use of the "r" word when I reached the final few chapters of "The Call of Silent Love" - a book by Carthusian monks who live a life of solitude (if you click on the "Carthusian Spirituality" label at the bottom of this post, you will be linked to my earlier posts about the Carthusians). If anyone has the right to use the word "radical" in connection with their faith, it is the Carthusians.

The Carthusians use the word "radical" to explain the life-changing effect that God's grace has on our lives (I've highlighted the "r" word when it us used):

"The Christian, through union with Christ in baptism and sanctifying grace, participates in the life of Christ. We receive within ourselves a new life-principle, the Holy Spirit, new faculties for knowing with God's knowledge and loving with God's love. The light of faith opens on to the mystery of the human being and God. The unfolding of this life at once assumes and surpasses natural human life; in this we see our deepest desire fulfilled although it is hidden and cannot be realized by natural powers alone.

There is both continuity and radical disjunction. In the deepest reality of the human face is traced the image of God, thanks to an increasingly profound conformity with Christ, effected interiorly by the Spirit (2 Corinthians 3:18). Up to this point the self had struggled for self-affirmation in all the riches of its personality. The Gospel demands that we lose our life to gain it, so that it may be 'no longer I but Christ who lives in me.' The center around which our being is organized is henceforth no longer our self but Christ.

At every level there is radical transcendence. Let us go through the list from top to bottom. The great strength of affirmation and aggression that is found in us reaches paradoxical fulfillment in self-abnegation, obedience, gentleness, humility, and forbearance. The lust for possessions ends in the freedom of voluntary poverty, the thirst for knowledge in silence before the mystery, the desire for communion of love in the purity of the total gift of self to the Other." (pp. 167-68, 170)

"Radical transcendence" - that's a use of the "r" word I think I can accept. Let's just hope I don't over-use it.

Sunday, June 2, 2013

The Spirituality of Silence

As a child growing up a farm, far away from other people and activity, I often longed for noise. Now, I often find myself longing for silence.

My longing for silence has made this passage from 1st Kings one of my favorites:

(The Lord said): “Go out and stand on the mountain before the Lord, for the Lord is about to pass by.” Now there was a great wind, so strong that it was splitting mountains and breaking rocks in pieces before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind; and after the wind an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake;and after the earthquake a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire; and after the fire a sound of sheer silence.When Elijah heard it, he wrapped his face in his mantle and went out and stood at the entrance of the cave. Then there came a voice to him that said, “What are you doing here, Elijah?” (1 Kings 19:11-13).

Many people in our society do not know how to handle silence, and the prospect of sheer silence can be overwhelming. Contemplative silence, however, can "truly effect a foretaste of heaven" (The Call of Silent Love, p. 10).

Martin Luther did not think much of the monastic practice of silence: "Away, therefore, with the silly and silent monks who suppose that worship and saintliness consist in silence!" (Luther's Works Vol. 3, p. 200). Contrary to Luther, I think that worship can be done beautifully in silence. There is a scene from the movie "Into Great Silence" which illustrates the beauty of silence, as the silence of the cloister is so intense that you can hear the snow fall, and is only interruped by the occasional ringing of the bell:

In "The Call of Silent Love" it is written that Carthusian "piety was fed by the common resources of the Church: the liturgy, the sacraments, the Word of God, Christ. Their silence was not mute but resounded with celebration and the praise of God." (pp. 7-8).

My longing for silence has made this passage from 1st Kings one of my favorites:

(The Lord said): “Go out and stand on the mountain before the Lord, for the Lord is about to pass by.” Now there was a great wind, so strong that it was splitting mountains and breaking rocks in pieces before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind; and after the wind an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake;and after the earthquake a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire; and after the fire a sound of sheer silence.When Elijah heard it, he wrapped his face in his mantle and went out and stood at the entrance of the cave. Then there came a voice to him that said, “What are you doing here, Elijah?” (1 Kings 19:11-13).

Many people in our society do not know how to handle silence, and the prospect of sheer silence can be overwhelming. Contemplative silence, however, can "truly effect a foretaste of heaven" (The Call of Silent Love, p. 10).

Martin Luther did not think much of the monastic practice of silence: "Away, therefore, with the silly and silent monks who suppose that worship and saintliness consist in silence!" (Luther's Works Vol. 3, p. 200). Contrary to Luther, I think that worship can be done beautifully in silence. There is a scene from the movie "Into Great Silence" which illustrates the beauty of silence, as the silence of the cloister is so intense that you can hear the snow fall, and is only interruped by the occasional ringing of the bell:

In "The Call of Silent Love" it is written that Carthusian "piety was fed by the common resources of the Church: the liturgy, the sacraments, the Word of God, Christ. Their silence was not mute but resounded with celebration and the praise of God." (pp. 7-8).

Monday, May 27, 2013

Christian Renewal From the Desert - Carthusian Spirituality

"All Christian renewal expresses itself by an exodus into the desert" - A Carthusian.

Several months ago, a young man from the neighborhood named Jeremy stopped into our parish office and told our administrator that he wanted to talk to the pastor. Because of my day job, I don't spend a lot of time in the office at St. Luke, but I just happened to be there that day. Over the next 30 minutes or so, Jeremy told me how he was trying to discern his calling, and how he had been reading the Desert Fathers and Thomas Merton.

We hit it off, and the next time we met, he showed me another book he was reading, "The Call of Silent Love." The interesting thing about this book is that there was no author listed - the book simply noted that it was by "A Carthusian" and was translated from French to English by "An Anglican Solitary." Jeremy's introduction of this book to me has opened up a new and fascinating world - the world of Carthusian spirituality.

I knew a little about Carthusuan spirituality, mainly through watching the documentary film "Into Great Silence"

The film does a beautiful job of documenting the contemplative life of the Carthusian monks at their Grande Chartreuse monastery in France, but it does not attempt to explain why the monks live that life. I ordered a copy of "The Call of Silent Love" and, as beautiful as the film is, the book is perhaps an even greater example of the beauty of the Carthusian life.

The book begins by explaining the beginnings of the Carthusian order, as founded by St. Bruno in the Eleventh Century. Essentially, the Carthusian order represents a radical return to the spirituality of the desert, where the monks live a life marked by prayer, contemplation, and silence. While they follow a similar pattern of daily prayer to Benedictines, they do not follow the Rule of St. Benedict; instead, they follow their own rule called the "Statutes."

In coming blog articles, I will write about some of the details of Carthusian spirituality, but for now, I will begin with a taste of the kind of beauty found within the book. Here is the book's description of their monastic setting:

"The valley is narrow and has something of the clear sightlines of a cathedral nave about it: a vault of light encased within steep walls rising 1000 metres like arms outstretched in prayer.

The first hermitage was built at a spot higher up the valley, in the sanctuary. Great trees upheld the vault of heaven. Water poured from a crystal fountain. The incense of smoke from wood fires rose slowly. The small sounds of the natural world only enhanced the silence, an attentive listening to all that is. A place of prayer, a place of God. One could not live there without being marked by the One who dwells there." (p. 5).

So, thank you to Jeremy for getting me to read about the beautiful world of the Carthusians.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)